Apple’s conflicts with government regulators can often seem like a classic case of an unstoppable force meeting an immovable object. Thanks to its dominance in the tech market, the company has increasingly found itself in the crosshairs of countries from around the world, who are concerned with everything from alternative payments in the App Store to interoperability with other messaging platforms.

The problem is that even when regulators seem to win, the results they end up with are often very different from what they probably intended, even if Apple’s concessions meet the letter of the law. As recently as last week, the Cupertino-based company made changes to the way that it handles some areas where regulators had intervened, but in true corporate fashion, those alterations are minimized to the extent that they will hardly have the impact that regulators would likely have preferred.

Link to the future

One of the most contentious aspects of the App Store is the way Apple polices how developers can interact with their customers. For example, if you want to access ebooks via your Kindle app or stream TV and movies via your Netflix app, you can certainly download the appropriate software to your iOS device. But once you do, you’re presented with little more than a login screen and scant information about how to manage your account if you need to.

Pursuant to a deal with the Japan Fair Trade Commission last year, Apple announced that it would be making a worldwide change to allow what it calls “reader apps”—i.e. those apps that let you access media from what is usually a paid subscription service—to provide a link out to their site. Even mentioning within an app that users can visit a service’s website has long been verboten on the App Store, for reasons that Apple claims have to do with security and ease of use but also smack of the company trying to prevent developers from sidestepping having to pay the commission that Apple levies on any commerce through its storefront.

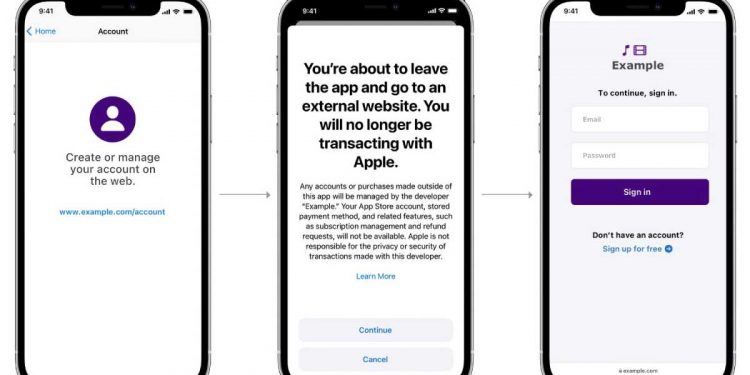

Unfortunately, the resulting change is—as should have probably been predicted—the bare minimum. Apple has implemented strict rules about these external links, not only restricting them to reader apps (via an “entitlement” that must be approved by the company) but also limiting it to a single link that must be accessed by way of a dialog box whose scaremongering text is specified by Apple.

Suffice it to say, this limited concession is unlikely to change the status quo for Apple or app developers.

Reader apps are allowed to provide links to outside sites for transactions, but the UI Apple makes developers use seems like an attempt to scare the user.

Apple

You’re gonna pay one way or another

Over in the Netherlands, a related challenge is far less oblique than the JFTC’s objection. An ongoing battle in the country has seen Apple repeatedly fined for not satisfactorily implementing a system to allow alternative methods of payment in dating apps. The company previously made an adjustment that allowed dating app providers to offer payment either via the App Store or alternatives, but Dutch regulators stipulated both should be allowed within the app.

After racking up a €50 million fine (in terms of the company’s bottom line rather insubstantial), Apple has relented and said that it will meet the restrictions set out by the country, though its subsequent proposal has yet to be detailed.

I wouldn’t hold my breath. In this case, as in so many others, Apple seems to have taken on the air of a toddler, testing its limits to see exactly what it can get away with. When it did allow for those alternative payments system, Apple “generously” reduced its App Store commission from 30 percent to 27—a difference precisely in line with the roughly 3 percent charged by payment processors, as if to reinforce the idea that payment processing is only a small part of its platform value.

Message therapy

It’s examples like this that don’t bode well for future regulation of tech behemoths. Case in point: the Digital Markets Act being enacted by the European Union. Among the ideas included in this far-ranging legislation is that messaging platforms like WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, and Apple’s own iMessage should have to be interoperable with each other, as well as smaller services.

Should Apple be forced to make iMessage work with third-party messaging apps like WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger, it’s not hard to imagine more bubble colors coming to Messages.

Should Apple be forced to make iMessage work with third-party messaging apps like WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger, it’s not hard to imagine more bubble colors coming to Messages.

Apple

Should this end up being enacted and required to be enforced, it seems clear that Apple will do the minimum possible to adhere to those rules. Which would probably include throwing up warnings about communicating insecurely with users that aren’t on Apple’s service, and probably tinting message bubbles from third-party services a frightening shade of red.

And thus we get to the root of the problem: the people in charge of regulating and legislating these kinds of changes might mean well, but they fundamentally don’t understand technology well enough to not only formulate their rules effectively but also fundamentally to even ask the right questions about how they can accomplish their goals.

This doesn’t necessarily mean they should abrogate their responsibility altogether and let tech companies regulate themselves: we’ve already seen how that’s working and the answer is generally not great. But just as those big tech companies finagle their taxes to pay as little as they can legally get away with, loopholes and inspecific regulations allow them to do the bare minimum, without even getting close to fixing the underlying problem.

Source by www.macworld.com