One thing that everyone agrees on is that sleep, and especially REM sleep, does matter. For one thing, evolution wouldn’t have favored such a dangerous activity — in which we are disconnected from reality, sitting ducks for accidents or predators — if it weren’t deeply helpful for survival. It can’t be an accident that so many animals, including humans, devote enormous chunks of their lives to sleeping. In fact, science has yet to discover an animal that doesn’t sleep at all. (One outlier is a 1967 study that suggested that bullfrogs don’t sleep; it is now considered to have been flawed.) Migrating birds and swimming dolphins manage to sleep while on the move by resting one hemisphere of their brains at a time. Sitting ducks do this, too — they take turns on guard duty. There’s also a less successful version of the phenomenon in humans, known as the “first-night effect,” which occurs when the left hemisphere of our brains refuses to fully rest when we’re sleeping in a new, uncertain environment for the first time, causing us to wake up tired. Even jellyfish sleep, despite not having brains, and earthworms that don’t get a chance to sleep for several hours after experiencing a stressful event, like extreme heat, cold or exposure to toxins, are less likely to survive. One study, using a magnetic device called the insominator, tested the effects of sleep deprivation on honeybees and found that it made them bad at communicating with the rest of their hive. Another found that rats deprived of all sleep will be dead within a month.

In humans, shorter sleep is associated with heart disease, obesity, stroke and Alzheimer’s, and various studies have suggested why: Sleep is when the brain does much of its “housekeeping,” allowing our bodies to secrete growth hormone, to produce antibodies and regulate insulin levels and to repair neural cells and remove waste proteins that build up in our brains. It’s also critical to lots of intellectual and emotional processing; without enough sleep, it’s harder for us to learn new things, evaluate threats, deal with change and generally control our emotions and behavior.

Still, none of that means that the dreams that happen during sleep — their content or even their existence — are meaningful in their own right. As Zadra explained to me, “Sleep could do all its stuff without us having these virtual simulations,” these elaborate narratives unfolding inside our heads every night. Anyone making the case that dreams matter, therefore, has to grapple with that fundamental question of content. Is there a point to spending our nights inside strange, phantasmagoric stories that we rarely even remember the next day?

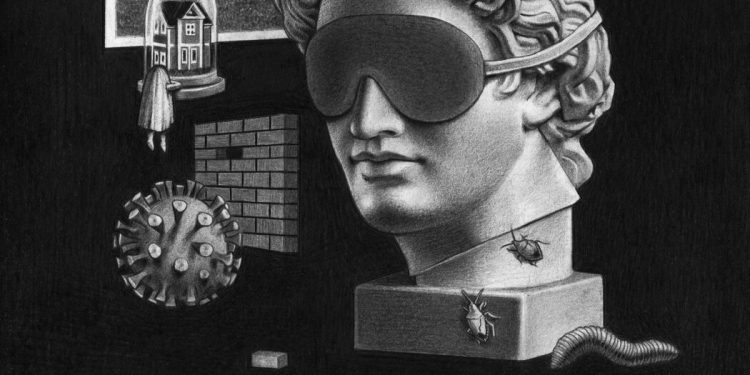

Within a week of her library dream, Barrett posted a survey online. Along with basic information about the dreamers who filled it out — where they lived, whether they worked in health care, if they had been sick — she gave people the space to describe any recent dreams they believed to be about the pandemic. In many, the connection was obvious: dreams of working in an I.C.U. or getting a positive Covid test or hiding from disease. (Barrett was collecting dreams in English, which, she acknowledges, created biases in the data, as did self-selection by participants who — presumably — cared about the pandemic, had an interest in dreams and consumed the sorts of news media that might point them toward her work.) Other dreams were more metaphorical but still offered intuitive connections, the kind of transference of emotions that dream researchers are used to identifying. A common dream of this type involved monsters lurking just out of sight, or invisibly attacking the people around them; in one dream, the invisible monster could kill only people who were within six feet of its most recent victim. Barrett also noticed a surge in bug imagery, often scary swarms of insects, which she chalked up to the dreaming mind searching for visual representations to match the fear it felt, and landing on a pun — a virus, after all, is known as a bug.

Still other supposed connections to the pandemic, though intuited by the dreamer, were not clear to Barrett. (For example: a dream in which Oprah Winfrey threatened a gymnasium full of people with a hand-held circular saw.) But many people took pains to explain the connections that they saw in their own dreams, like when a bat entered a dreamer’s house and the dreamer used a thick copy of The Washington Post to swat it. The fear, during the dream, was of rabies, but waking up brought instant recognition that bats were also a possible source of the virus that causes Covid-19. The dreamer speculated that the dream “perhaps symbolizes the need to arm oneself with information, data and knowledge to protect against an invisible virus quickly circulating way too close to home.”

Some days dreams arrived by the hundreds, and it took Barrett hours just to read through them all. She began to note themes and similarities, which she later explored through statistical and linguistic analysis. Women, who according to other studies experienced more job loss and more pandemic stress than men, also saw their dreams change more: Their levels of anxiety, sadness and anger were much higher than the prepandemic dreams with which Barrett compared her new sample. (Women also had most of the anxiety dreams about home-schooling.) And the dreams of the sick, as is common when the body is fighting a fever, were the most bizarre and yet the most verisimilar of all — vivid-but-strange hallucinations that made it difficult to separate sleep from waking life. A Covid patient named Peter Fisk described feeling wide awake, curled up in bed and thinking fondly back to his days of living in a cozy den in a riverbank. “But then,” he wrote, “it occurred to me that I had never actually done that. I was having false memories of being an otter.”

As was the case with post-9/11 dreams, the most affected dreamers were those living closest to trauma. More than 600 health care workers sent in dreams, which Barrett recognized as often the same story, told with small variations: “There’s a critically ill patient in their care, something is not working and the patient is dying. They feel desperately responsible and yet have no control over death.” Research has shown that the dreams of trauma victims often start by replaying the traumatic event in great detail, but over time they often incorporate more and more new elements and story lines, blunting the emotion of the original dream. (Some therapists encourage this evolution, coaching patients to imagine, and then to try to dream, more empowering endings to their traumas.) In cases of post-traumatic stress disorder, however, this process seems to break down; the classic PTSD nightmare is a realistic, flashbacklike trauma that repeats again and again with few alterations.

Source by www.nytimes.com