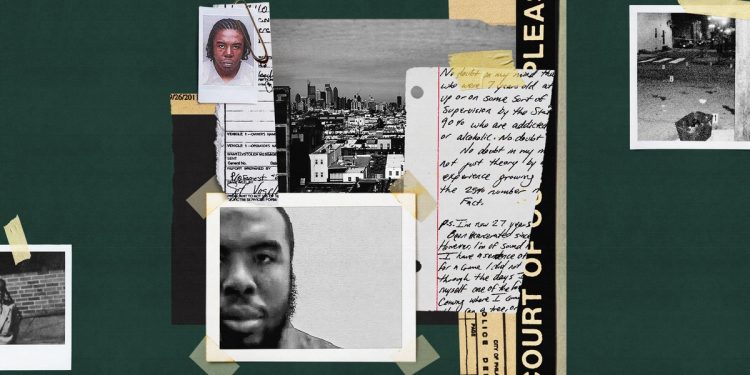

Last week, The Atlantic published its November cover story, “Good Luck, Mr. Rice,” in which Jake Tapper investigates the case of a Philadelphia teenager who was convicted of attempted murder after a 2011 shooting that left four injured. C. J. Rice, now 28, has maintained his innocence. No physical evidence tied him (or anyone) to the crime, and the single eyewitness who identified him as the perpetrator had told police three times that she did not recognize the shooter before ultimately changing her story. Rice’s pediatrician, who happened to be Tapper’s father, Theodore, contends that his involvement would have been physically impossible—Rice himself had been seriously injured in a separate shooting three weeks earlier.

A skilled lawyer would have emphasized these holes in the state’s case. But Rice’s court-appointed attorney, Sandjai Weaver, was not up to the task of zealously defending her client. Overworked and underpaid, she failed to prepare alibi witnesses, challenge the credibility of the eyewitness’s testimony, or even introduce his medical records as evidence. “Rice lacked legal representation worthy of the name,” Tapper argues. “And as he has discovered, the law provides little recourse for those undermined by a lawyer. The constitutional ‘right to counsel’ has become an empty guarantee.”

Rice first appealed his conviction in 2013. At the time, an older man gave him what he calls an “athar,” a prison adage imparted from inmate to inmate (athar may derive from the Arabic athara, meaning “transmit” or “pass along”). The appeals process, the man said, was like a boxing match: Each time you get knocked down, it will be harder to get back up. If Rice wanted his freedom, he would have to shake off the disappointments, drag himself to his feet, and keep fighting.

That initial appeal, and another challenging Weaver’s competency, have since failed. Rice has struggled, at times, to rouse himself after a defeat. But in each of the letters we’ve exchanged, he’s assured me that he’s “just taking things one day at a time.” It’s a difficult coping strategy for someone facing 30–60 years in prison.

His appeals exhausted, obtaining a commutation from the governor is likely Rice’s only path to freedom. (In Pennsylvania, those currently incarcerated must have their sentence commuted before seeking a pardon.) Commutation is a complicated and lengthy process. Unlike his counterparts in many other states, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf cannot commute sentences unilaterally. The state constitution prevents the governor from acting without the approval of a five-member Board of Pardons, composed of the lieutenant governor and attorney general as well as a medical expert, corrections expert, and victim representative. The petition process requires painstaking attention to detail—one man I spoke with said his petition was rejected because of a single mistyped date—and great patience. It usually takes about three and a half years to unfold.

On Friday, Rice and a team of lawyers at an organization called the Reform Alliance began that process, sending a petition for commutation to the Board of Pardons. The success or failure of Rice’s petition will depend on the underlying facts of his case, but also on the members of the board and the political pressures they face.

Though the board was created in the 19th century to forestall favor granting and horse trading, the process has hardly been insulated from politics. Two of the current board members, Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman and Attorney General Josh Shapiro, are in the final weeks of competitive campaigns for elections that are of national significance—Fetterman in a race that could determine control of the U.S. Senate, Shapiro in a race against a gubernatorial candidate who denies the results of the 2020 election. For Fetterman, past votes in support of commutation applications have proved to be potent attack-ad fodder for his opponent, the celebrity doctor Mehmet Oz. Shapiro’s opponent, as well, has cast him as soft on crime, linking rising rates of certain crimes to Shapiro’s tenure as attorney general. Both Fetterman and Shapiro declined to comment on Rice’s case, claiming they were hesitant to weigh in on an application that could come under their review.

Rice’s petition is unlikely to be reviewed before November’s elections, however, after which the composition of the board will shift. Voters will decide the political futures of Fetterman and Shapiro and whether the two men will pay a price for their choices as board members. The candidates for lieutenant governor and attorney general will undoubtedly be watching. The lessons they learn from the experiences of their predecessors will shape the outcome of Rice’s last attempt to secure his freedom.

A commutation petition requires a detailed account of the applicant’s personal and criminal history. When the board receives an application, it solicits supplemental materials and feedback from the department of corrections as well as the district attorney and president judge for the county where the crime occurred. It then votes on whether to allow an applicant’s case to proceed. If the applicant wins the requisite number of votes—a simple majority in C.J.’s case—they receive an interview with the board and a public hearing. Afterward, the board votes again: If an applicant wins the support of enough members, the board recommends their case to the governor. Only at that stage can the governor decide to issue a commutation.

Though the creation of the board was intended to make the clemency process less subjective, its members lack a definitive set of factors for determining whether to recommend an applicant. Its mandate, former board members told me, is simply to “show mercy.”

I reached out to former board members to ask about how they would view a case like Rice’s. John Wetzel, who served as Pennsylvania secretary of corrections and sat on the board as its “corrections expert” from 2007 to 2011, expressed disbelief at the facts of Rice’s case. “I’ve been working 32 years inside corrections,” Wetzel said. “There are still moments that shock you.”

Members of the board serving in elected positions may share Wetzel’s view, but their calculus is complicated by the realities of Pennsylvania politics. The positions that Fetterman and Shapiro currently hold are common launchpads for higher office; over the past century, more than a quarter of Pennsylvania governors have at one time served as either lieutenant governor or attorney general.

Decisions made while serving on the Board of Pardons can come back to haunt an elected official. In 1992, a man named Reginald McFadden, who had been convicted of murder at age 16, petitioned the board to have his sentence commuted. Having received enthusiastic recommendations from his prison warden, the secretary of corrections, and the judge who had ordered his sentence, the Board of Pardons, then chaired by Lieutenant Governor Mark Singel, voted 4–1 to recommend McFadden’s commutation to then-Governor Bob Casey Sr. McFadden was released from prison in 1994.

That year, Singel was running as the Democratic candidate to succeed Casey as governor. A month out from Election Day, he maintained an eight-point lead over his Republican opponent, Tom Ridge. Then, on October 6, less than three months after his release, McFadden was arrested in New York and later convicted of the murder of two Long Island residents and the rape of a third.

The arrest turned the governor’s race upside down. Ridge went on the offensive, characterizing Singel as soft on crime. Ridge ultimately won the gubernatorial race by nearly 200,000 votes.

In 1997, the Pennsylvania legislature passed a constitutional amendment that required a unanimous vote of the Board of Pardons for the governor to commute a life sentence or the death penalty. Between his election in 1994 and the end of his term, Ridge did not commute a single prisoner’s life sentence.

For members of the Board of Pardons with political ambitions, the lessons of the Reginald McFadden case were clear. One wrong vote could sink an entire career.

After the 1997 constitutional amendment, commutation for those with life sentences became virtually impossible to obtain. From its passage through 2018, the board has been able to muster unanimous votes for only 12 life-without-parole applicants. At least eight others would have qualified for a recommendation under the old rules; the amendment functionally condemned each of them to die in prison. Commutations for people like C. J. Rice, serving long sentences for violent crimes, have been nearly as hard to secure.

As lieutenant governor, John Fetterman has prioritized revitalizing the clemency process. Fetterman made criminal-justice reform a central tenet of his 2018 campaign and has sought to redefine the Board of Pardons as a final fail-safe in cases where courts have declined to act.

In April 2019, Fetterman appointed Brandon Flood as the board’s secretary. Flood had himself been incarcerated and successfully applied for a pardon. He brought to the role a litany of ideas for reforming the process. Facing a backlog of cases from the ’90s and early aughts, he wanted to impose a minimum eligibility requirement to ensure that the board focused its efforts on those who had served the most time; he pushed to clear administrative red tape and reduce and remove filing fees. The fear of recidivism that dominated the board in the shadow of the McFadden case was unmerited, he argued. According to a study Flood helped commission as secretary, of the 3,037 pardon applicants in the state of Pennsylvania from 2008 to 2018, only two were convicted again of a violent crime.

Together, Fetterman and Flood dramatically increased the number of applicants that the board recommended to Governor Tom Wolf. Wolf, for his part, tended to follow the board’s recommendations, issuing more than 100 pardons each year of his term. In 2020, he granted 551. (A spokesperson for Wolf said that “the governor has made criminal justice reform a top priority throughout his administration” but declined to address Rice’s specific case.)

Fetterman was especially passionate about the case of Lee and Dennis Horton, two brothers convicted of second-degree felony murder in 1994. The Hortons were identified by an eyewitness in a “show-up” procedure that is now commonly regarded as likely to induce bias—similar to the way an eyewitness later identified C. J. Rice. Their clemency application failed when Shapiro voted against it. According to The Philadelphia Inquirer, Fetterman then met with Shapiro and threatened to run against him in the 2022 Democratic gubernatorial primary unless he changed his vote on theirs and other applications. The brothers got a new hearing, and Shapiro voted to recommend them for commutation. When they were released from prison, Fetterman hired them as field organizers for his campaign. (Fetterman declined to comment to the Inquirer on private conversations with Shapiro. A spokesperson for Shapiro denied that the encounter ever happened and said Shapiro’s votes had nothing to do with politics.)

Once Fetterman’s term on the board expires, the reforms that he and Flood enacted may prove fleeting. “There’s a lot of stuff you can do administratively or that you can do through executive order, but it’s not durable policy,” Flood, who resigned from the board in 2021, told me last week. “After you leave in January, whoever the next person is can say, ‘I don’t like this shit,’ roll it back, and that’s it.”

The Republican nominee for lieutenant governor, Carrie DelRosso, has been mum on what she would do as pardon-board chair, telling the Delaware Valley Journal that she is “very pro–law enforcement” and would “listen to the experts.” Though she and Doug Mastriano, the party’s nominee for governor, diverge on many issues—candidates for governor and lieutenant governor run on separate tickets in Pennsylvania primaries, and Mastriano had endorsed a less moderate candidate for lieutenant governor—neither has much of an incentive to continue Fetterman’s reforms if elected.

The Democratic candidate for lieutenant governor, Austin Davis, has also been vague. Asked whether he would use the lieutenant governor’s office “as a bully pulpit for criminal justice reform and clemency,” as Fetterman has, Davis told the Pennsylvania Capital-Star that he is “very concerned that Pennsylvania communities are safe.” “I believe there isn’t an and-or situation when it comes to safety and the work of the Board of Pardons,” he said.

Flood told me he’s met with both lieutenant-governor candidates about the pardons board. Neither DelRosso nor Austin knew much about how the executive-clemency process worked, he said, but they were willing to learn.

Still, even if the next lieutenant governor were to fully share Fetterman’s sympathies, they may be hesitant to replicate his approach to the board, having seen its effects in his own campaign for Senate.

Recently, Mehmet Oz’s campaign reportedly paid actors to dress in prison jumpsuits and carry signs that read Inmates for Fetterman. Seizing on his hiring of the Hortons, the campaign has demanded that Fetterman “fire the convicted murderers on his staff.”

Accurate or not, Oz’s attacks appear to be resonating: Though Fetterman once maintained a healthy lead, polls have tightened in recent weeks, leaving the outcome of the Senate race unclear.

For now, Rice remains at State Correctional Institution–Coal Township. As his case proceeds, he’ll sit in his cell and try to remember his fellow inmate’s athar. “I’m not bitter,” he told me in March. “I see what that does to people in here, people who are locked up for stuff that they didn’t do.” He sighed. “People really lose their mind in this place.”

Rice has little choice but to wait out the results of the 2022 election from the prison and watch as two newly elected politicians fill Shapiro and Fetterman’s vacated seats on the Board of Pardons. Ultimately, his fate will be decided by that board, by the political pressures that shape its decisions, and by how its members evaluate who deserves mercy.

The Reginald McFadden case still casts a shadow over Pennsylvania’s pardon process. So long as an elected lieutenant governor and attorney general serve on the board, so long as their positions launch careers in higher office, the board’s actions will be circumscribed by fears of making a similar mistake

In 2017, former Lieutenant Governor Mark Singel reflected on his decision to recommend McFadden for commutation in an essay published by America, a Jesuit monthly. “As much as I regret that fateful decision, I cannot accept the alternative: a government and a society that looks with cold indifference at those who have turned their lives around and who languish in our overcrowded prisons,” he wrote. “For me, mercy and compassion are more than personal options,” Singel continued. “They are the underpinnings of what can make America not only great but good.”

Source by www.theatlantic.com