It was Friday, 13 October 1972, and Fernando Parrado sat down in row nine of the plane about to depart from Montevideo to Santiago de Chile.

His best friend, Panchito, asked him to change seats so he could be at the window and see the scenery.

Panchito died when the plane crashed.

After the accident, Parrado was in a coma for four and a half days, but he recovered, only to find himself alone in the middle of the Andean mountains.

He survived for 72 days where no one is expected to — at an altitude of more than 3 000 metres, without proper equipment, water, and food, at the age of 22.

He hiked for ten days, 45 kilograms lighter, to look for help, crossing mountains and glaciers that the most experienced mountaineers fear.

Fernando Parrado, or Nando, as his friends call him, is one of the 16 survivors of one of the most incredible stories of the last century.

Fifty years after the accident, Parrado says that for him, on this date, there is nothing to commemorate but rather to pay tribute to those who were left behind.

“I shouldn’t be talking to you. I should be dead. Buried in a glacier 50 years ago,” he told Euronews.

‘The least likely survivors’

Parrado was a young player in an amateur rugby team in Uruguay. Along with his sister and mother, he was among 45 people on their way to Chile to play a match with their national champions.

In the middle of the journey, while flying over the Andes mountain range, the turbulence began.

“Plane crashes are always caused by a combination of things: an underpowered plane, loaded to the limit, bad weather, a crew that is not as experienced as it should be, etc.” he said.

The aeroplane experienced a downdraft, and as it flew out of the cloud cover, it became clear to everyone on board that the Andes were not just appearing to be very close. The impact was, in fact, unavoidable.

The plane they were travelling in crashed in the far west of Argentina, about 150 km south of Santiago de Chile. 33 people initially survived, albeit some had serious injuries.

“We crashed in the middle of the Andes mountains,” says Parrado. “We were the least likely group to have to endure those conditions.”

One of the biggest challenges was the inclement weather. On the snow-covered landscape, temperatures reached minus 30 degrees Celsius. “We came from the beach, from Montevideo, and 95% of the guys had never touched snow or seen a mountain in their lives.”

Today, “thanks to technology, this tragedy would have been over in 8 or 10 hours”.

Parrado remained in a coma for the first four days, in what he describes as an “absolute black hell”.

When he woke up, the first thing he discovered was that his mother and sister Susi, as well as his two best friends, Panchito and Guido, were dead.

“In civilisation, I might have broken down in a way that I wouldn’t have been able to get up, but I didn’t have the time for that,” Parrado said.

Fernando maintains that the survival instinct did not let him think about anything other than figuring out how to get out of there.

“My mind only allowed me to focus on fighting the cold, the hunger, the fear, the uncertainty.” The pain of losing his loved ones came later.

After a week, they received the news over the radio that the teams were abandoning the search and would wait until the end of the austral winter — that runs from June through August in the southern hemisphere — to look for the bodies.

“At that moment I almost panicked, but I remembered that panic kills you, and fear saves you,” Parrado explained.

At 3,575 metres above sea level, with no protective clothing and no sight on the horizon because of the glaciers around them, the group of survivors decided to wait until summer to escape.

Parrado believes that the trust, empathy and friendship that existed in the group were key elements to their survival.

Parrado confesses that the icy winds were not the only enemies they had to face: “Not knowing when you’re going to eat again is the most frightening fear a human being can have.

“It’s a terrible anxiety that you can’t understand until the body begins to self-consume.”

There were still two months before the weather improved, so the survivors had to resort to feeding on the bodies of their dead friends. “We all made an absolutely unimaginable pact, we were the first people who consciously donate our bodies (so others could live).”

The most difficult decision

As time passed, the weather improved, but there were only 16 survivors left — less than half of those who survived the impact.

For Parrado, it was at this point that the most difficult decision came: to leave the fuselage of the crashed plane and go in search of help.

He still does not know how he could have taken such a risky decision — whether it was fear or courage that drove him off that glacier.

“Maybe it was my love for my father; I just wanted to go back to him,” Parrado said.

He and his friend Roberto Canessa set off in search of help.

The third member of the three-man search party, Antonio Vizintin, had to return, as there simply wasn’t enough food.

Having to trek through the Andes meant both of the young men were over-encumbered in layers upon layers of jeans and sweaters, with their weakened bodies suffering with each step.

“I think only Roberto and I know what it’s like to reach the real limit because there was no physical strength left in us. I lost 45 kilos, and my skin, my hair, my shoes were weighing me down. But we couldn’t stop.”

After ten days of trekking, a miracle happened.

The young men reached a mountainside and spotted a riverbank.

It was Canessa who, looking north, saw a Chilean arriero or muleteer — a person who transports goods by mule, commonly found in South America — Sergio Catalán, on his horse on the other bank.

Despite Parrado and Canessa’s best efforts, the distance between the two banks meant that Catalán could not understand what they were saying, or rather, he simply could not hear them.

“But Sergio Catalán had a lot of common sense: he picked up a stone, wrapped a paper and a pencil around it, and threw it across the river”.

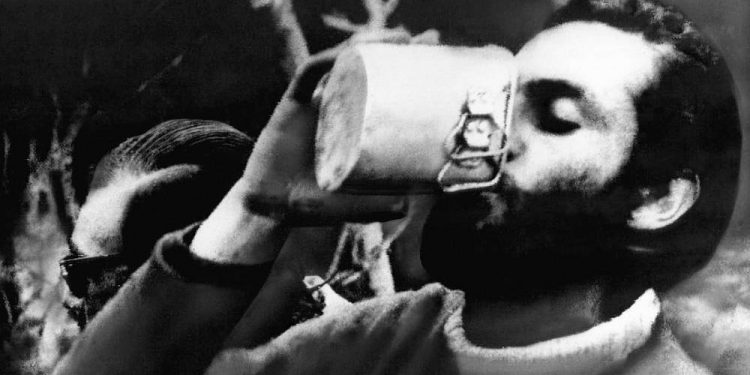

Parrado, who did not even sign the note in all the haste, wrote: “I come from a plane that fell in the mountains. I am Uruguayan, I have 14 friends up there. Please, we can’t leave, we are hungry”.

Catalán quickly threw them two loaves of bread and set off in search of help to Puente Negro, a town ten hours away by horse and carriage.

Parrado and Canessa did not know it at the time, but the rescue teams arrived the very next day.

‘I wouldn’t change a thing’

Parrado recalls that the rescuers could not believe they were the passengers from the plane that had crashed two and a half months earlier.

The Chilean Air Force came in with three Bell UH-1 helicopters to assist with the rescue, and Fernando and Roberto told the pilots where the rest of their companions were.

Parrado guided two of the helicopters using a pilot’s chart, and the rescuers were astounded how anyone managed to survive at the crash site for so long.

“One pilot told me that this was the worst flight of his life because they simply couldn’t make out where they were going,” Parrado said.

After his stay in the hospital, where they took away the clothes he had been wearing for 72 days, he returned home.

“When we returned to Uruguay, my brothers in the mountains were embraced by their families. I arrived home, and my father was in a state of despair, because he had lost his entire family.”

On 13 October 2022, Fernando Parrado says he had no regrets about what happened. “Thanks to our friends, 16 of us got out, and now, together with our families, we are 140 people,” he said.

Parrado never forgot his experience in the mountains. He also never lost his connection to those who were his support in the darkest moments.

“We are a group of people in a very close brotherhood — if something happens to someone, the others are immediately there to support them,” Parrado said. “We survived together, and after all this time, we are still united”.

In the years after his rescue, Parrado tried his hand at a career as a professional race car driver but eventually decided to grow his father’s business instead, becoming a television personality in the process.

He is also a motivational speaker, and he co-authored a book about his experience in the Andes called Miracle in the Andes: 72 Days on the Mountain and My Long Trek Home.

Fifty years after the tragic accident, Parrado does not deny that what they lived through was traumatic: “Compared to what we lived through, hell is a comfortable place.”

But when asked if he would change anything about the past, the survivor is clear about his answer.

“Thinking about the past is insane,” he said.

“I wouldn’t change anything at all because changing the past would mean not having the family I have now.”

Source by www.euronews.com